How Does Encryption Work, in Theory?

There are many kinds of encryption used in our everyday communication. Online and offline, over the internet and in person. In this article, I will explain the basics of how encryption should work in theory. I explain in this article why encryption is important, and why you should care about it.

We will start by looking at in-person, offline encryption.

Cryptography We Do Everyday

We encrypt things all the time without even thinking about it. If you spend a significant amount of time with the same group of friends, you will tend to develop common codes that may not make sense to others outside the group. For example: for years, my family called sombody falling from a sitting position “doing a Don”. There is a story of course—We knew a guy named Don who fell from his plastic beach chair in a rather hilarious way; “doing a Don” was born.

These types of minor dialects in speech are cryptographic in their own way. The truth is though, that we use cryptography much more than that!

“Is cryptography any different than talking? We say something other than what we mean, and then expect everyone is able to decipher the true meaning behind the words. Only, I never do…” — Adapted from a scene in The Imitation Game (p. 39-40)

How many times have you hinted, flirted, and innuendoed to try to say “I find you very physically attractive”? Have you told your friend that always stinks to wear more deodorant? Have you ever had someone say the words “I’m fine” when you know for certain that they are indeed not okay?

| Words Said | Meaning |

|---|---|

| What can you do? | I don’t want to talk about this anymore. |

| I don’t want to overstay my welcome. | I want to go home now. |

| I don’t like them and don’t know why. | They threaten my ego. |

| Creepy | Unattractive and friendly |

All of these scenarios are perfect examples of lies encryption! If we have the key to these codes, we can start to understand what people really mean.

Hopefully I have convinced you that you use deceit cryptography on a regular basis in your life, so let us consider what a basic encryption method might be:

Grade-School Encryption

Back when I was in middle school I used to pass notes like these:

This is a message encrypted using the Caesar cipher. This encryption technique was used by Julius Caesar during the reign of the Roman Empire to “encrypt messages of military significance.”[1] This is one of the oldest and simplest methods of encryption known to us today.

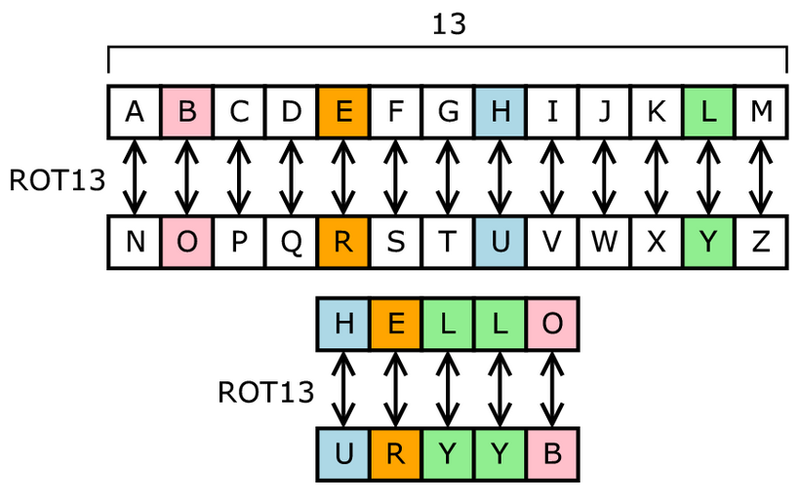

You can try this out yourself by moving some letters forward in the alphabet. An ‘A’ turns into a ‘B’, ‘B’ into ‘C’, ‘C’ into ‘D’, et cetera. In this case, “Hello!” would become “Ifmmp!” That is just using a shift of one. You can use a shift of seven, for example, and then you would shift letters like so:

A -> +7 -> HQ -> +7 -> XT -> +7 -> A

When you reach the end of the alphabet, wrap around to the beginning to find the encrypted letter.

Example of a Caesar Cipher

Let’s setup a little story to illustrate the problems of encryption. We will have three characters:

- Alice, young lady with feelings for Bob

- Bob, a young lad with an addiction to pancakes

- Eve, a wee jealous girl scout who sits between Bob and Alice

Alice really likes Bob and wants to tell Bob her feelings, so she writes “I love you, Bob! Please eat healthier!” on a sticky note. She passes it to Eve, so Eve can pass it to Alice’s love interest. However, in an unfortunate turn of events Eve reads the note herself, and decides not to give it to Bob.

Oh the horror! Alice is without young love! How could she remedy this so that Bob can read her message, but evil Eve can not? Let’s use the Caesar cipher to fix this problem.

Let us assume that Alice and Bob already have a shared key, 7 for example. To encrypt this message, she should shift her letters seven letters forward in the alphabet—just like the example above.

![A longer Ceasar cipher encrypted message: ROT2: Wpeng Vgf ku dqqogt ogog]](/assets/img/ceasar2.jpg)

Now Alice’s message reads “P svcl fvb, Ivi! Wslhzl lha olhsaoply!”

Now, when Alice sends her Romeo a little note, all he has to do is decrypt the text by shifting the letters down by 7. Here is a site which can do longer pieces of text for you instead of doing it manually.

Problems

Before the two love-birds start smooching on the branch of a big pine tree in the schoolyard, perhaps we should consider some problems with the Ceasar cipher.

It is Very Easy to Break

Even Eve with her measly grade 4 math skills could easily start going through this message with pen and paper and figure out any combination in a couple hours at maximum. Imagine how easy this is for a computer? This could be broken in a few microseconds even on an older processor like the Intel Core 2 Duo.

No Secure Way of Sharing Keys

We assumed in our previous example that Bob and Alice already have a shared key (seven) to encrypt and decrypt all of their messages. If Bob and Alice did not have a previous friendship and time to share secrets of this sort, there is no way to share their key with eachother without Eve also knowing. This would defeat the entire purpose of obscuring the message in the first place.

Universal Vulnerability of Messages

Every message sent between the two parties uses the same code to encrypt and decrypt. If someone finds out the code once, all previous communications are comprimised.

Better Encryption Methods

To combat the issues with easily breakable, shared-key cryptography, we can turn to the beautiful beast that is Asymetric Cryptography. I will discuss this more in another article, but for the technically inclined:

- RSA/EC provides very large cryptographic keys. It would be impossible for a human to encrypt or decrypt a message manually.

- Asymetric cryptography provides four keys, instead of just one; stopping evesdroppers from listening in on your secret conversations—even if you do not have the chance to exchange keys in advance.